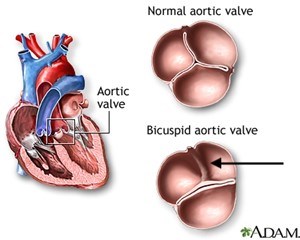

What is Bicuspid Aortic Valve (BAV)?

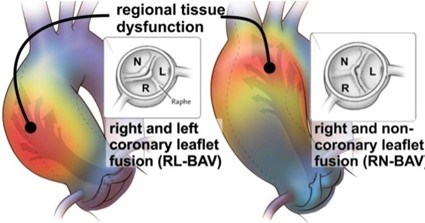

Bicuspid aortic valve (BAV) is a condition in which a person is born with an aortic valve with two aortic valve cusps, or leaflets, instead of the normal three cusps (Figure 1).

BAV is one of the most common congenital heart valve disorders (present at birth) and occurs in about 1 out of every 100 births. It’s about 2 to 3 times more common in males than females. Because a BAV leads to abnormal aortic valve function, the majority of people with a bicuspid aortic valve will have to undergo heart surgery to replace (or repair) the abnormal valve at some point in their life. This condition can lead to aortic regurgitation or insufficiency. This is when blood finds its way back into the heart instead of being pumped to the rest of the body. In some people, a severely leaking aortic valve causes symptoms when the affected person is young. More commonly, the BAV slowly develops a gradual thickening of the valve leaflets over time leading to a progressive narrowing or restriction of the valve opening (aortic valve stenosis). When a severely narrowed (or stenotic) BAV leads to a weakening of the heart muscle or causes symptoms such as shortness of breath, chest pain, or fainting spells, the valve must be replaced. When a severely leaking or regurgitant bicuspid valve leads to symptoms or to progressive heart enlargement, the valve must be replaced (or repaired).

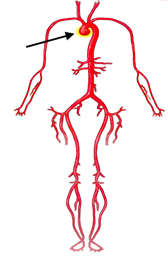

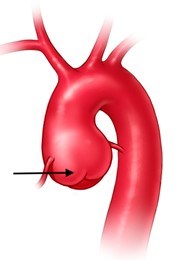

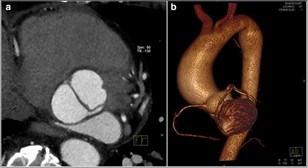

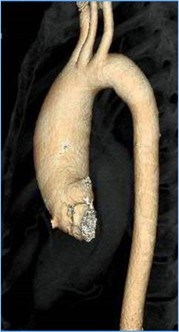

In some people, the bicuspid aortic valve is also associated with thoracic aortic aneurysm disease. The aorta is the largest blood vessel in the body and carries oxygen-rich blood away from the heart to the body (Figure 2). The aorta arises from the heart above the aortic valve to form the aortic root and ascending aorta and curves toward the back at the aortic arch and descends in front of the spine (called the descending aorta) to the abdomen (abdominal aorta), eventually dividing to form the two arteries to the legs. The normal aorta is about 30 to 35 mm (almost 1.5 inches) in diameter at the beginning in the ascending aorta and it gets smaller the farther it is from the heart. When the aortic size is at least 50% larger than normal, it is called an aneurysm. Bicuspid aortic valve is associated with aortic enlargement and aneurysms of the ascending aorta (Figure 3).

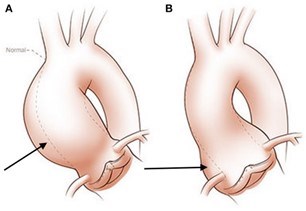

There are different reasons why a BAV can lead to the development of an aortic aneurysm. First is the hemodynamic theory; the abnormal shape of the BAV leads to increased turbulence of the blood being pumped from the heart into the aorta. Instead of being ejected normally into the aorta, the blood is pumped more towards one side of the aorta. This can lead to an increase in stress on that aortic wall (often the outer curvature), and over time, this abnormal stress can make the aorta weaker (Figure 4). This in turn can lead to aortic enlargement or even the formation of an aneurysm.

Another theory for why BAV may be associated with aneurysms of the aortic root and/or ascending aorta is known as the genetic theory. BAV may run in families, meaning when one family member has a BAV, the chance of another family member having the condition is higher than in the general population. There is almost a 1 in 10 chance for a first-degree relative (such as a parent, sibling, or child) of the person with a BAV to also have a BAV. In addition, the presence of both a BAV and thoracic aortic aneurysm (TAA) may also run in the family. In some of these families, a specific mutation in a gene is present which leads to the BAV and aneurysm disease. However, in most families with a BAV (with or without a thoracic aneurysm), genetic testing does not find a mutation in a specific gene. Even though most people with a BAV and an aneurysm will not have a family history of this condition, it is important to evaluate all first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, and children) for this possibility with an echocardiogram.

Even when a BAV and TAA disease runs in a family, a specific mutation in a gene responsible for this condition is not usually found in the family. Nonsyndromic hereditary thoracic aortic disease (nsHTAD) may have an increased chance of having a BAV. Mutations in ACTA2, MYH11, MAT2A, and LOX genes have been found in a small number of individuals with familial TAA and BAV disease (Figure 5). In addition, people with Loeys-Dietz syndrome due to mutations in TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD3, TGFB2, and TGFB3 have a higher chance of having a BAV than the general population. In some people with a BAV and aneurysm, the enlargement of the aorta is largest and most pronounced at the very beginning of the aorta in the aortic root. People with aortic root aneurysms may have a higher chance of finding a specific genetic mutation responsible (Figures 3 and 8).

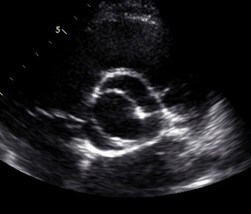

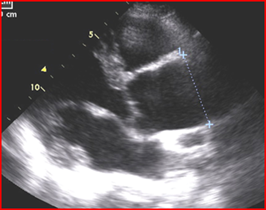

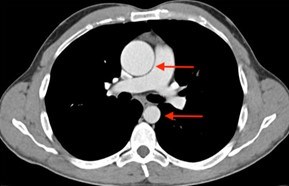

Evaluation of the aortic valve and heart function by an ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) is recommended (Figures 6-7). If the full extent of the ascending aortic size is not adequately seen on the echocardiogram (Figure 8), then further evaluation with a CT angiogram (Figure 9 and Figure 10) or MR angiogram is recommended.

Because BAV with TAA is a risk factor for a tear in the aortic wall (aortic dissection), aortic surgery to replace the aortic root and/or ascending aorta is recommended when the aorta reaches 5 to 5.5 cm in diameter, depending upon individual circumstances. Surgery at 5 cm or more should be considered for those with a family history of aortic dissection, those with rapid aortic growth rates (more than 3-5 mm in a year), or if the operation can be performed at low risk in a center of excellence (a cardiac surgeon and hospital that has a lot of experience with these type of surgeries). Other risk factors for BAV-related aortic complications include the presence of coarctation of the aorta, a congenital defect in which the descending aorta is narrowed or constricted. If a specific gene mutation is found responsible for BAV with aneurysm, then the genetic condition may influence the timing of aortic aneurysm surgery.

How common is BAV?

Bicuspid aortic valve is present in about 1% of the population. It is 2 to 3 times more common in males than in females.

What are the features of BAV?

- BAV may be suspected based upon hearing a heart murmur with a stethoscope, but not all people with a BAV have an abnormal cardiac examination. Therefore, the diagnosis requires an echocardiogram or other imaging, such as a CT scan or cardiac MR. (Figures 6-10 above)

- The BAV may function normally for a long time and not be diagnosed or suspected until testing is performed.

- The BAV may cause a heart murmur (abnormal heart sound) due to blood leaking backwards across the valve (aortic regurgitation or insufficiency) or abnormal narrowing of the valve (aortic stenosis).

- The BAV can be associated with other congenital heart defects including coarctation of the aorta (which is a narrowing or constriction of the initial part of the descending aorta).

- The BAV is a risk factor for an infection on the aortic valve (infective endocarditis).

- The BAV is associated with enlargement (dilatation) or aneurysm of the ascending aorta (Figure 3, 8, 9, 10).

- BAV is a risk factor for aortic dissection (a tear in the aortic wall) when a thoracic aortic aneurysm is present (Figure 11).

What are the genetics of BAV?

In most cases, a bicuspid aortic valve and thoracic aortic aneurysm occurs by chance and a specific genetic mutation responsible for the condition is not discovered or present. When someone has a BAV, there is a 9% chance of a first-degree relative (such as a parent, sibling, or child) also having a BAV. In some families, BAV and aortic root and/or ascending aortic aneurysm run in the family. Therefore, it is recommended that first-degree relatives be evaluated with an echocardiogram (and sometimes with a CT or MRI scan) to see if BAV and aneurysm is present. Mutations in some genes associated with familial or hereditary thoracic aortic aneurysm disease may also be associated with a BAV. These include ACTA2, MAT2A, MYH11, LOX, and the Loeys-Dietz syndrome family of genes (TGFBR1, TGFBR2, SMAD3, TGFB2, TGFB3).

What testing is needed?

- An ultrasound of the heart (echocardiogram) is recommended to evaluate the BAV, the heart function, the aortic root and ascending aortic size, and to evaluate for coarctation of the aorta.

- If the ascending aorta is not seen adequately on the echocardiogram, then a CT scan or an MRI of the chest should be performed.

- Long-term follow-up of the aortic valve and aortic size should be performed in those with BAV at an interval depending upon one’s current condition.

- Screen (with an echocardiogram) all first-degree relatives (parents, siblings, children) to determine if anyone else in the family has a BAV and/or an enlargement of the ascending aorta.

- Consider performing genetic testing if there are features suggesting Loeys-Dietz syndrome or if nonsyndromic heritable thoracic aortic disease is found after family screening. The chance of finding a specific genetic mutation may be higher if there is an aortic root aneurysm associated with a BAV.

How is BAV and/or ascending aortic aneurysm treated?

- If high blood pressure (hypertension) is present, treatment to reduce the blood pressure to normal is recommended. If high blood pressure is associated with a leaking BAV (aortic regurgitation or insufficiency), then blood pressure control with an ACE inhibitor, an angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), or a calcium channel blocker (like amlodipine) is recommended.

- Having a BAV increases the lifetime risk of developing an infection on the heart valve called endocarditis. Methods to lessen the risk of endocarditis include good dental care, including flossing and routine dental cleanings. The most recent guidelines do not recommend routine antibiotic prophylaxis (taking a preventative antibiotic) before dental procedures when a BAV is present.

- Surgery to replace (or repair) the ascending aortic aneurysm may be required if symptoms are present due to severe valve dysfunction or if the heart muscle has enlarged or weakened.

- Surgery to replace the ascending aortic aneurysm with a graft may be required if the aorta has enlarged to a significant size. The size for aneurysm surgery depends upon many factors.

- If aortic valve surgery is required and the aortic size is > 4.5 cm, then aneurysm surgery is usually performed at the same time.

- If the aortic aneurysm is > 5.5 cm/m, it is reasonable to consider surgery.

- If the aortic aneurysm is > 5.0 cm and there are other risk factors for aortic dissection present (such as a family history of aortic dissection or rapid growth of the aorta), or if surgery can be done at a low risk to the patient at a center of excellence, surgery to remove the aneurysm may be considered.

Are there limitations on exercise?

- An individual with a BAV may participate in all types of sports and exercise as long as the aortic valve is functioning fairly well and there is no significant aortic enlargement or aneurysm present.

- If the BAV has significant leaking (regurgitation/insufficiency) or narrowing (stenosis), there are restrictions on certain types of exercise and physical activities.

- If an aortic aneurysm is present or if severe valve dysfunction is present, intense weightlifting and competitive athletics, especially those which involve bursts of activity, straining, or higher levels of activity, should be avoided. In general, low to moderate levels of recreational exercise is often appropriate. Individuals should discuss the specific circumstances of their condition with their physician before beginning exercise.

How does having a BAV/TAA affect one’s ability to start a family?

- When significant valve disease is present with a BAV and/or if an aortic enlargement or aneurysm is present, it is recommended that a consultation with cardiology, high-risk obstetrics, or a maternal-fetal medicine specialist be obtained before considering pregnancy. Management during pregnancy may include medication adjustment, serial imaging of the aortic valve and aorta, and methods to lesson labor and delivery as appropriate.

- If the aortic is significantly dilated, a doctor may recommend against pregnancy.

What are the signs and symptoms of an acute aortic event?

There is a very low risk of acute aortic dissection when a BAV is not accompanied by a thoracic aortic aneurysm. When significant aortic enlargement or aneurysm is present complicating a BAV, there is a risk of aortic dissection (or a tearing of the wall of the aorta) (Figures 11-12). Symptoms of an acute dissection typically include the abrupt onset of a severe pain in the chest, back, neck, and/or abdomen. The pain may be described as sharp, severe, or tearing and may be associated with shortness of breath or a sense of doom. Immediate medical attention is required with imaging of the aorta (typically by a contrast CT scan) to determine if an aortic dissection is present. Aortic dissection involving the ascending aorta requires emergency cardiac surgery. The aortic valve may require replacement at the same time.

Where can I learn more about BAV?

The Marfan Foundation: https://www.marfan.org/bicuspid-aortic-valve

Up To Date:

Citation: Braverman AC, Harris KM, Kovacs. RK, Maron BJ. Eligibility and Disqualification Recommendations for Competitive Athletes With Cardiovascular Abnormalities: Task Force 7: Aortic Diseases, Including Marfan Syndrome. A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association and American College of Cardiology. 2015;66:2398-2403.

Get the latest news on genetic aortic and vascular conditions

If you have an interest in advancing the research, education, and treatment of genetic aortic and vascular conditions, sign up for emails from the Genetic Aortic Network using the form to the right.

These communications are geared toward professionals and include information such as updates to best practices and treatment guidelines, upcoming scientific and clinical webinars, and newly developed tools for healthcare professionals and researchers.

Join the GenTAC Alliance Mailing List